Several years ago when I was pursuing my MFA at Hunter, I attended these research seminars that were meant to show the many resources available to us as creative writers. I tried to make the best use of that time, attempting to find records of my paternal grandfather’s work as a civil engineer in Burma, before he quit to join the Freedom Movement in India. I was looking for historical documents that could shed light and add detail to tidbits of family narrative. Most of my searches came up empty then. I sent queries to other librarians, historians and scholars about my particular interests in Burmese Public Works projects and life in the 1920s and 1930s. The responses I received were warm and inquisitive. While they themselves did not have information that could help me, most thought my best bet would be the India Office at the British Library. Since then, I’ve gathered more fragments of family history about this time which resulted in some answers, but even more questions, pointing me once again to the British Library. So here I am in London with the support of a Literature Travel Grant (Thank you Jerome Foundation!)

The vastness of the collections housed here—the legacy of colonialism—is both impressing and unsettling. With a list of questions and gap-filled narratives, I arrived at the library with both hope in the possibility of what I might find, but also fear of what I may not. The fear is two-pronged: 1) that some records are truly and forever lost and 2) that they are in fact here, but I won’t be able to find them.

I have spent a great part of the past year perusing historical records from a much smaller archive researching a different writing project, and even on that small scale, I never felt I had enough time to satisfy my increasing curiousity. How does one even begin navigating the archives of an empire? The British Library can be a bit overwhelming and distracting for inquisitive and wandering minds. I’m trying to stay focused on the quest at hand, and not veer off into the stacks on Tamil literature, the encyclopedia of Hindu Architecture or Indian Cinema. I thought I’d share some of my experiences from my first day.

To access the Asian and African Studies Reading Room, where the India Office Records are held, you need to register for a reader pass. This process is similar to going to the DMV, but much more pleasant. You need two forms of photo ID, one with a signature and one with a home address (US Passport and Driver’s License should do the trick). You’ll be asked to fill out an online form at a computer station. (Note that British keyboards are a little different– it took me a moment to locate the @ sign near where a semicolon usually resides). After submitting your form, you’ll be assigned a number and once it’s called, a staff member will ask you a few questions, take your picture and give you a reader pass ID card. The pass is valid for a year. (If you are a graduate student working on your doctorate, yours will be valid for 3 years.)

Cloakroom and Locker Room

You are not allowed to bring much into the reading room. So you can either check items in the Cloakroom or store them in

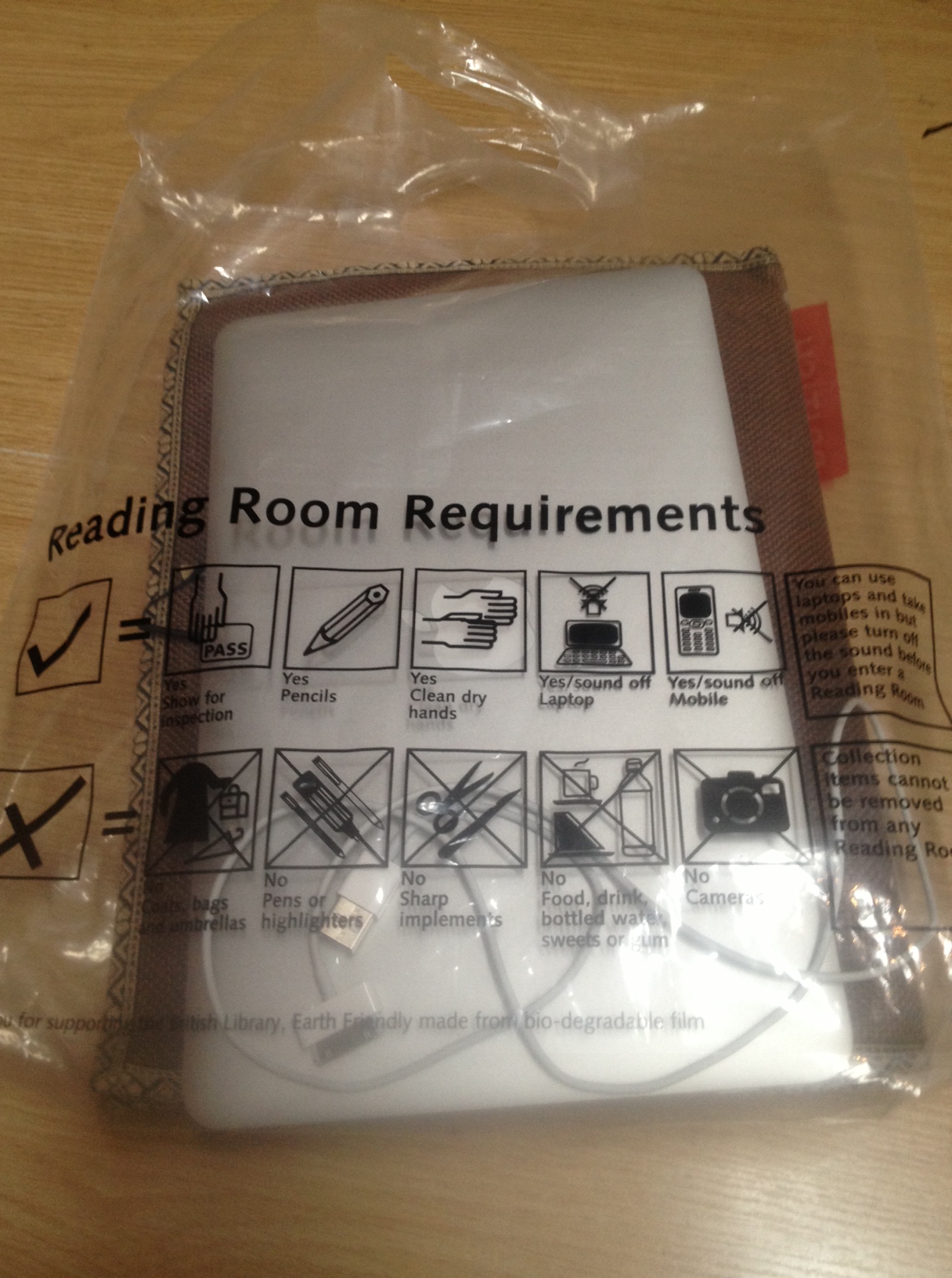

You are not allowed to bring much into the reading room. So you can either check items in the Cloakroom or store them in  the Locker Room. No bags, coats, pens, sharp objects, cameras, or scanners are allowed inside the reading room. I was really excited about using my new Vu Point Magic Wand Portable Scanner here, so that was a big disappointment. You can bring your phone, but can’t use its camera (another disappointment.) Prepping to go into the reading room is a bit like going through airport security. Anything you are bringing into the reading room (laptop, pencils, books, charging cables,) must be placed in a clear plastic bag.

the Locker Room. No bags, coats, pens, sharp objects, cameras, or scanners are allowed inside the reading room. I was really excited about using my new Vu Point Magic Wand Portable Scanner here, so that was a big disappointment. You can bring your phone, but can’t use its camera (another disappointment.) Prepping to go into the reading room is a bit like going through airport security. Anything you are bringing into the reading room (laptop, pencils, books, charging cables,) must be placed in a clear plastic bag.

Getting Started on the Quest

I had previously been in touch over email with the BL reference librarians and they’ve given me some starting points for my research.

I had previously been in touch over email with the BL reference librarians and they’ve given me some starting points for my research.

“If your grandfather was employed as an engineer in Burma by the British Government he “may” appear in either the Burma V/12 (History’s of service) or V/13 (yearly civil lists) series. These can be researched when you visit us in person.”

So this is where I began. Once you locate the document record number, you can request the file online. You are only allowed 10 items a day, and it takes 70 minutes to deliver your records. (A friend commented that this was to allow for tea breaks). The engineer in me started to do some mental math and strategic planning noting all the constraints- 10 records a day, an hour and ten minutes to retrieve them, open 10am-5pm on Monday; 9:30am-5pm Tues-Sat, closed on Sunday and planned Strike on Wed… (Is this why they issue passes for a whole year?)

I was looking at information over the course of 20 years for each of these two data sets, but didn’t want to use 40 record requests to barely scratch the surface on this initial query, so I opted to triangulate the data, and request a few files in the beginning, middle and end of this time period, to see if in fact these volumes yielded any information at all.

While waiting for these volumes, I moved on to the next set of files, suggested to me by another reference librarian.

“India Office responsibility for Public Works, such as bridge and road building, was transferred in 1926 from the Public Works Department to both the Economic Department and the Financial Department. The Economic Department Annual Files (series reference IOR/L/E/8) are currently in the process of being catalogued in detail, so they are mostly not yet on the online catlogue. It is a similar situation with the Financial Department Annual Files (series reference IOR/L/F/6). When you visit the British Library, you could have a look at the contemporary indexes and registers for these two records series for the 1930s, for any files on the construction of the bridge. There is a handlist in the Asian & African Studies Reading Room which gives the volume references for each year.”

The economic development file registers contained listings of reports on various topics: agriculture, aviation, cotton, correspondence/communications, census, copyright, customs and duties, collections and economics, electricity, factories, forests, finance, irrigation, Imperial Institute, insurance, jute, lighthouses, land labour, League of Nations, medical, mines and minerals, merchandise, missions, motor vehicles, opium and drugs, oil , plants, ports and harbors, posts and postal, industrial property, patents and design, prohibition, rice, research, rubber, shipping, salt, sanitary , seamen, sugar, tariff, trade agreements, tea, telegraphy,veterinary and the United Nations.

There wasn’t much on public works, but I was curious about the lighthouse reports. My aunt and uncle who are twins were born in Tavoy, where my grandfather was building a lighthouse. I discovered these two records:

- IOR/L/E/9/414 1926-1936 Collection 70/3 Lighthouses-Indian Lighthouse Act of 1927, with terms of appointment for chief inspectors of lighthouses

- IOR/L/E/9/415, 1938 Collection 70/4 Lighthouses-General Lights in Burma: administration after 1 Apr 1937, following separation of Burma from India

My curiousity about their content was followed by more disappointment. “(Missing)” was written after the titles of these reports. They weren’t found in the online request register. One librarian said “So much was lost or destroyed during the war.”

Delivery of Records

After this unfruitful search of the economic development files, we decided to break for lunch, and upon our return my earlier requested items were ready. I started an excel spreadsheet with different tabs for each set of files I was researching (Histories of Service, Yearly Civil Lists, Economic Development files). I listed each record, year, whether or not I requested it yet, date of request, and was eager to fill remaining columns on what was discovered.

I started first with the 1920 and 1932 History of Service volumes. These records listed names of civil servants and a brief resume of their record of service, and dates of service within each post. Each volume was 3-4 inches in thickness, organized by field of service. I flipped through the pages eagerly but found no record of “Engineers” among the civil servants. It was again a familiar feeling of loss. No luck with this volume, I switched to the volumes of yearly lists of public servants. I had requested 1921, 1932, and 1933. I wasn’t sure of the date of when he started, so decided to skip to the middle records to see if I could find him.

In the 1933 set, I came across a section titled “Burma Engineering Service” and poured over these pages intently, scanning them looking for a name.I was nervous and emotional anticipating finding him and not. What if he’s not here? But maybe he is…

I was searching for any mention of “Iyer” or “Narayanan” I knew my grandfather’s name to be M.S. Narayanan Iyer. It was only the day before this trip to London, that I asked my mother what M.S. stood for. What she told me were the two words now staring back at me on the page: Manakkal Sundaralingam Narayanan. (Thanks Mom!)

Listed under Class II, Assitant Engineers, I found my grandfather!

The civil yearly lists were also formatted in spreadsheet fashion. Name, Date of Appointment to Department, Date of Promotion to Present Grade, Station, Remarks. The 1932-1933 files told me this:

Mannakal Sundaralingam Narayanan B.E. M.E. (h.), (b.) was appointed to the service on October 31, 1919, promoted to his present grade on February 1, 1921, Stationed in Tavoy, (South Subdn, Tavoy Dn.) [There’s a handy list of abbreviations at the front of these records. My grandfather had a Bachelor’s and Master’s Degree in engineering and passed an examination in Hindustani and Burmese, but at a lower standard than if he had a capital H. and B. next to his name ]

The 1921 file lists his name as M.S. Narayanan (had I started here, perhaps it would be have been easier to recognize, but it was an amazing feeling to discover the words Manakkal Sundaralingam). In 1921, he was stationed in Rangoon in the Lighthouse Subdivision. From 1920-1933 he was at the same grade which earned 300 to 800 Rs a month.

Copying Records

The reading room was about to close when I made this discovery. I tried to make a photo copy of these pages and the self-service machines, but this is something I wasn’t allowed to do myself with these records and had to request the library to do for me, with more forms and paperwork and at price of 0.67 pounds a page (about a dollar/page) They will be ready on Monday after 3pm. (Sigh. I really wish scanners were allowed) Looking at the room of researchers, most people sat with their laptops or with pencil and paper, and opted to manually copy or type text from the manuscripts they were perusing.

In the remaining minutes of the reading room hours, I made some additional online requests for volumes to be available on my visit on Monday.Upon leaving, the woman at the entrance desk searched my clear plastic bag, flipping through a book on Burma I brought in with me, making sure I didn’t sneak any records out between the pages. Then, we retreated to collect our bags in the locker room, which at closing time was reminiscent of high school. A dismissed class of researchers packing up their bags after the bell.

Next Steps

I can’t yet fully explain how elated I was to discover the row carrying the briefest of details of my grandfather’s service. It is only the beginning of my quest here, but significant to me for many reasons.

On Monday I will visit the other IOR/V/13 yearly lists to sketch a history of his service, and then tackle the IOR Public Works Department annual files [IOR/L/PWD/6 ] to get as many details on this work. I also hope to meet with a library curator who contributes to the Untold Lives Blog, which highlights BL records, researchers and the hidden stories they are unearthing.

With the finite time I have left, I’m trying to employ a method to navigating these archives, organizing my queries, and compiling the results. Yet at the same time, I’m sending a warm invite to Serendipity to join me. I have some extra room in my clear plastic bag.

Researching the India Office Records at the British Library: Time and Timelines

Deciphering Place in Numbers- A Rosetta Stone in Annual Budget Reports

Great post! Fingers crossed you get a ton of research done tomorrow (monday). Ter and I are looking forward to reading more about your fact hunting.

Wonderful and exciting research. Thanks for sharing!